SOUTHERN SLAVS IN UTAH

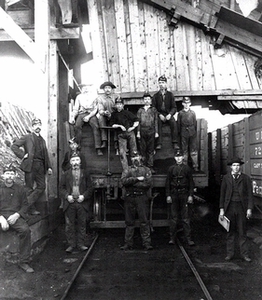

Miners, including Southern Slavs, at Scofield

Southern Slavs, comprising Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs, formed another aspect of the "new" immigration that arrived in Utah in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As with other southern and eastern European groups, South Slavs were drawn to Utah for its mining and railroading opportunities. The first wave arrived in the late 1890s, congregating in the coal-mining regions of southeastern Utah, particularly Carbon County. These peoples, labeled as "Austrians," were a significant force in the Carbon County coal mines in the 1903-04 strike. Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs came from Austria-Hungary, from the provinces of Croatia-Slavonia, Carniola, Dalmatia, Bosnia, and Herzegovina. They generally came from farming villages that were homogenous in their particular culture, language, and religion. Serbs were Serbian Orthodox, while Slovenes and Croats were Roman Catholic. Slavic immigration into Utah was but one manifestation of a general Southern Slav population movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

First attracted to the East and Midwest, many Southern Slavs left communities there to seek greater opportunities in the American West, including Utah. In addition to Carbon County, these immigrants traveled to Ogden, working for the Union Pacific Railroad, and to the mines of Bingham Canyon, Alta, and Park City, as well as to the smelters of the Salt Lake Valley. A second wave came to Utah in the period prior to World War I. A pattern of migration developed between the mining areas of Utah, Colorado, Montana, and Nevada. The flow was based upon the seasonal demand for coal, causing men to migrate to metal-mining areas when coal mines experienced a slowdown.

As families were formed, many made the decision to stay in the area. Institutions were solidified or formed to help deal with a new environment; they included the idea of godfatherhood and the extended family, while fraternal organizations and boardinghouse life also created bonds. The extended family proved of particular importance, providing a needed sense of security. The clustering of these groups was evident in Utah, particularly among the Serbs and Croats in Bingham Canyon and Midvale, and among the Slovenes in Carbon County.

The metal-mining community of Highland Boy attracted southern Slav miners and became an area of settlement for various extended families. By 1908 more than half of the town's population was comprised of Serbs and Croats, who held "old world" grudges and hatreds against each other. The situation became especially exacerbated because they were living in close proximity without the benefit of other immigrant groups present to lessen the tension, which began to wane after World War I. Joe Melich, owner of the Serb Mercantile Company, became an ardent spokesman for the Serbs in Bingham Canyon. In 1920 he was elected president of the Serb National Federation. The community of Highland Boy proved significant in that it contained a large number of Southern Slavs, outnumbering other groups, and the area remained a fertile ground for inter-group strife.

Midvale, with its American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO), attracted numerous Slavs. Young single men came to work in the smelter and lived in boardinghouses or with married southern Slavic couples. Women especially bore the burden of caring for these boarders. While necessary, both landlords and boarders viewed this as only a temporary condition. Industrial life caused a change in old-world institutions such as the saloon. In Midvale, the Slavic saloon often operated on a day-long basis instead of with an emphasis on evening hours as in the old country. Also, such places functioned as havens from the unfamiliar world. Within their confines, discussions could take place and decisions made in a familiar environment.

One development of these encounters was the creation of social and fraternal organizations. In 1908 the Croats of Midvale affiliated with the Croatian Fraternal Union. The Serbs organized an independent organization called the Serbian Benevolent Society, which eventually affiliated with the Serb National Federation of Pittsburgh. Among other things, these associations provided needed life insurance to immigrants. Unlike the saloon, they functioned in a formal way and carried with them the respectability of the national organization. Leaders grew from the ranks: John Dunoskovich in the Croatian community, and George Lemich among the Serbs.

Religious life also adjusted to existent conditions. Croats, being Catholic, utilized various Catholic churches throughout the valley. In 1918 Ykov J. Odzich, a Serbian Orthodox priest, arrived in Midvale to tend to the needs of the Serbs; but through a series of unfortunate events his tenure did not last. However, the celebration of Christmas and Easter were important holidays among the South Slavs in Midvale, as elsewhere. The barbecued Easter lamb continued as an important cultural symbol.

Midvale held a central significance to southern Slavic settlement in Utah. It served as a place for both the arrival and dispersion of many Southern Slavs who immigrated to northern Utah. Carbon County was also important. Helper, a division point on the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad's main line, became a primary area of Slavic settlement. Work on the railroads brought Serbs, Slovenes, and Croats to southeastern Utah in the late 1890s. As the years progressed, the need for unskilled labor increased. By 1914 more than 500 Slav miners lived in the coal camps of Clear Creek, Winter Quarters, Sunnyside, and Castle Gate. Others settled into farming.

Helper grew as a town of immigrants; thus, business opportunities there were greater for Southern Slavs as well as for other nationalities. For example, the Mutual Mercantile Company was a joint venture of several partners, including J.P. Rolando, an Italian, and John Skerl, a Slovene. Fraternal and social organizations also rose to prominence. In 1904 the Slovenska Narodna Podporna Jednota (Slovene National Benefit Society) was created in Cleveland, Ohio, and soon local lodges were founded in Carbon County as well as in Bingham Canyon and Murray. This group served Slovenian workers. In the post-World War I period a large number of Slovenes came to Carbon County to join relatives. In addition, sizable numbers of Slovenes and Croats immigrated to Helper from the coal regions of southeastern Colorado.

Political and labor union involvement cut across intergroup lines. Southern Slav involvement in the strikes of 1903, 1922, and especially in 1933 proved significant. In 1933 Slavs were the main supporters of the National Miners Union strike that eventually led to the recognition of the United Mine Workers of America. The strike heightened awareness of the role of unionization, with Slavic women also taking an active part in the event.

The restrictive immigration legislation of the 1920s curtailed Southern Slavic immigration into Utah. However, the adaptation and accommodation of Southern Slavs to their conditions in Utah have been and continue to be dynamic. As has been the case with other immigrants, institutions often have been changed in form, but the values expressed continue to be basically the same. Since the early 1950s the Croats and Slovenes of Helper have supported the Slovenian National Home, a means to substitute a more useful and responsive community center for the local lodge. They have also established a yearly local folk foods festival, celebrating ethnic foods as well as dance, music, and art.

Disclaimer: Information on this site was converted from a hard cover book published by University of Utah Press in 1994. Any errors should be directed towards the University of Utah Press.