SEEd - Grade 3

SEEd - Grade 3

Printable Version (pdf)

Printable Version (pdf)

Course Introduction

Course Introduction

Utah Science with Engineering Education Standards

Utah’s Science and Engineering Education (SEEd) standards were written by Utah educators and scientists, using a wide array of resources and expertise. A great deal is known about good science instruction. The writing team used sources including A Framework for K–12 Science Education1, the Next Generation Science Standards2, and related works to craft research-based standards for Utah. These standards were written with students in mind, including developmentally appropriate progressions that foster learning that is simultaneously age-appropriate and enduring. The aim was to address what an educated citizenry should know and understand to embrace the value of scientific thinking and make informed decisions. The SEEd standards are founded on what science is, how science is learned, and the multiple dimensions of scientific work.

Principles of Scientific Literacy

Science is a way of knowing, a process for understanding the natural world. Engineering applies the fields of science, technology, and mathematics to produce solutions to real-world problems. The process of developing scientific knowledge includes ongoing questioning, testing, and refinement of ideas when supported by empirical evidence. Since progress in modern society is tied so closely to this way of knowing, scientific literacy is essential for a society to be engaged in political and economic choices on personal, local, regional, and global scales. As such, the Utah SEEd standards are based on the following essential elements of scientific literacy.

Science is valuable, relevant, and applicable.

Science produces knowledge that is inherently important to our society and culture. Science and engineering support innovation and enhance the lives of individuals and society. Science is supported from and benefited by an equitable and democratic culture. Science is for all people, at all levels of education, and from all backgrounds.

Science is a shared way of knowing and doing.

Science learning experiences should celebrate curiosity, wonder, skepticism, precision, and accuracy. Scientific habits of mind include questioning, communicating, reasoning, analyzing, collaborating, and thinking critically. These values are shared within and across scientific disciplines, and should be embraced by students, teachers, and society at large.

Science is principled and enduring.

Scientific knowledge is constructed from empirical evidence; therefore, it is both changeable and durable. Science is based on observations and inferences, an understanding of scientific laws and theories, use of scientific methods, creativity, and collaboration. The Utah SEEd standards are based on current scientific theories, which are powerful and broad explanations of a wide range of phenomena; they are not simply guesses nor are they unchangeable facts. Science is principled in that it is limited to observable evidence. Science is also enduring in that theories are only accepted when they are robustly supported by multiple lines of peer reviewed evidence. The history of science demonstrates how scientific knowledge can change and progress, and it is rooted in the cultures from which it emerged. Scientists, engineers, and society, are responsible for developing scientific understandings with integrity, supporting claims with existing and new evidence, interpreting competing explanations of phenomena, changing models purposefully, and finding applications that are ethical.

Principles of Science Learning

Just as science is an active endeavor, students best learn science by engaging in it. This includes gathering information through observations, reasoning, and communicating with others. It is not enough for students to read about or watch science from a distance; learners must become active participants in forming their ideas and engaging in scientific practice. The Utah SEEd standards are based on several core philosophical and research-based underpinnings of science learning.

Science learning is personal and engaging.

Research in science education supports the assertion that students at all levels learn most when they are able to construct and reflect upon their ideas, both by themselves and in collaboration with others. Learning is not merely an act of retaining information but creating ideas informed by evidence and linked to previous ideas and experiences. Therefore, the most productive learning settings engage students in authentic experiences with natural phenomena or problems to be solved. Learners develop tools for understanding as they look for patterns, develop explanations, and communicate with others. Science education is most effective when learners invests in their own sense-making and their learning context provides an opportunity to engage with real-world problems.

Science learning is multi-purposed.

Science learning serves many purposes. We learn science because it brings us joy and appreciation but also because it solves problems, expands understanding, and informs society. It allows us to make predictions, improve our world, and mitigate challenges. An understanding of science and how it works is necessary in order to participate in a democratic society. So, not only is science a tool to be used by the future engineer or lab scientist but also by every citizen, every artist, and every other human who shares an appreciation for the world in which we live.

All students are capable of science learning.

Science learning is a right of all individuals and must be accessible to all students in equitable ways. Independent of grade level, geography, gender, economic status, cultural background, or any other demographic descriptor, all K–12 students are capable of science learning and science literacy. Science learning is most equitable when students have agency and can engage in practices of science and sense-making for themselves, under the guidance and mentoring of an effective teacher and within an environment that puts student experience at the center of instruction. Moreover, all students are capable learners of science, and all grades and classes should provide authentic, developmentally appropriate science instruction.

Three Dimensions of Science

Science is composed of multiple types of knowledge and tools. These include the processes of doing science, the structures that help us organize and connect our understandings, and the deep explanatory pieces of knowledge that provide predictive power. These facets of science are represented as “three dimensions” of science learning, and together these help us to make sense of all that science does and represents. These include science and engineering practices, crosscutting concepts, and disciplinary core ideas. Taken together, these represent how we use science to make sense of phenomena, and they are most meaningful when learned in concert with one another. These are described in A Framework for K–12 Science Education, referenced above, and briefly described here:

Science and Engineering Practices (SEPs):

Practices refer to the things that scientists and engineers do and how they actively engage in their work. Scientists do much more than make hypotheses and test them with experiments. They engage in wonder, design, modeling, construction, communication, and collaboration. The practices describe the variety of activities that are necessary to do science, and they also imply how scientific thinking is related to thinking in other subjects, including math, writing, and the arts. For a further understanding of science and engineering practices see Chapter 3 in A Framework for K–12 Science Education.

Crosscutting Concepts (CCCs):

Crosscutting concepts are the organizing structures that provide a framework for assembling pieces of scientific knowledge. They reach across disciplines and demonstrate how specific ideas are united into overarching principles. For example, a mechanical engineer might design some process that transfers energy from a fuel source into a moving part, while a biologist might study how predators and prey are interrelated. Both of these would need to model systems of energy to understand how all of the features interact, even though they are studying different subjects. Understanding crosscutting concepts enables us to make connections among different subjects and to utilize science in diverse settings. Additional information on crosscutting concepts can be found in Chapter 4 of A Framework for K-12 Science Education.

Disciplinary Core Ideas (DCIs):

Core ideas within the SEEd Standards include those most fundamental and explanatory pieces of knowledge in a discipline. They are often what we traditionally associate with science knowledge and specific subject areas within science. These core ideas are organized within physical, life, and earth sciences, but within each area further specific organization is appropriate. All these core ideas are described in chapters 5 through 8 in the K–12 Framework text, and these are employed by the Utah SEEd standards to help clarify the focus of each strand in a grade level or content area.

Even though the science content covered by SEPs, CCCs, and DCIs is substantial, the Utah SEEd standards are not meant to address every scientific concept. Instead, these standards were written to address and engage in an appropriate depth of knowledge, including perspectives into how that knowledge is obtained and where it fits in broader contexts, for students to continue to use and expand their understandings over a lifetime.

Articulation of SEPs, CCCs, and DCIs

| Science and Engineering Practices |

Crosscutting Concepts |

Disciplinary Core Ideas |

Asking questions or defining problems:

Students engage in asking testable questions and defining problems to pursue understandings of phenomena.

Developing and using models:

Students develop physical, conceptual, and other models to represent relationships, explain mechanisms, and predict outcomes.

Planning and carrying out investigations:

Students plan and conduct scientific investigations in order to test, revise, or develop explanations.

Analyzing and interpreting data:

Students analyze various types of data in order to create valid interpretations or to assess claims/conclusions.

Using mathematics and computational thinking:

Students use fundamental tools in science to compute relationships and interpret results.

Constructing explanations and designing solutions:

Students construct explanations about the world and design solutions to problems using observations that are consistent with current evidence and scientific principles.

Engaging in argument from evidence:

Students support their best explanations with lines of reasoning using evidence to defend their claims.

Obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information:

Students obtain, evaluate, and derive meaning from scientific information or presented evidence using appropriate scientific language. They communicate their findings clearly and persuasively in a variety of ways including written text, graphs, diagrams, charts, tables, or orally. |

Patterns:

Students observe patterns to organize and classify factors that influence relationships

Cause and effect:

Students investigate and explain causal relationships in order to make tests and predictions.

Scale, proportion, and quantity:

Students compare the scale, proportions, and quantities of measurements within and between various systems.

Systems and system models:

Students use models to explain the parameters and relationships that describe complex systems.

Energy and matter:

Students describe cycling of matter and flow of energy through systems, including transfer, transformation, and conservation of energy and matter.

Structure and function:

Students relate the shape and structure of an object or living thing to its properties and functions.

Stability and change:

Students evaluate how and why a natural or constructed system can change or remain stable over time. |

Physical Sciences:

(PS1) Matter and Its Interactions

(PS2) Motion and Stability: Forces and Interactions

(PS3) Energy

(PS4) Waves

Life Sciences:

(LS1) Molecules to Organisms

(LS2) Ecosystems

(LS3) Heredity

(LS4) Biological Evolution

Earth and Space Sciences:

(ESS1) Earth’s Place in the Universe

(ESS2) Earth’s Systems

(ESS3) Earth and Human Activity

Engineering Design:

(ETS1.A) Defining and Delimiting an Engineering Problem

(ETS1.B) Developing Possible Solutions

(ETS1.C) Optimizing the Design Solution |

Organization of Standards

The Utah SEEd standards are organized into strands which represent significant areas of learning within grade level progressions and content areas. Each strand introduction is an orientation for the teacher in order to provide an overall view of the concepts needed for foundational understanding. These include descriptions of how the standards tie together thematically and which DCIs are used to unite that theme. Within each strand are standards. A standard is an articulation of how a learner may demonstrate their proficiency, incorporating not only the disciplinary core idea but also a crosscutting concept and a science and engineering practice. While a standard represents an essential element of what is expected, it does not dictate curriculum—it only represents a proficiency level for that grade. While some standards within a strand may be more comprehensive than others, all standards are essential for a comprehensive understanding of a strand’s purpose.

The standards of any given grade or course are not independent. SEEd standards are written with developmental levels and learning progressions in mind so that many topics are built upon from one grade to another. In addition, SEPs and CCCs are especially well paralleled with other disciplines, including English language arts, fine arts, mathematics, and social sciences. Therefore, SEEd standards should be considered to exist not as an island unto themselves, but as a part of an integrated, comprehensive, and holistic educational experience.

Each standard is framed upon the three dimensions of science to represent a cohesive, multi-faceted science learning outcome.

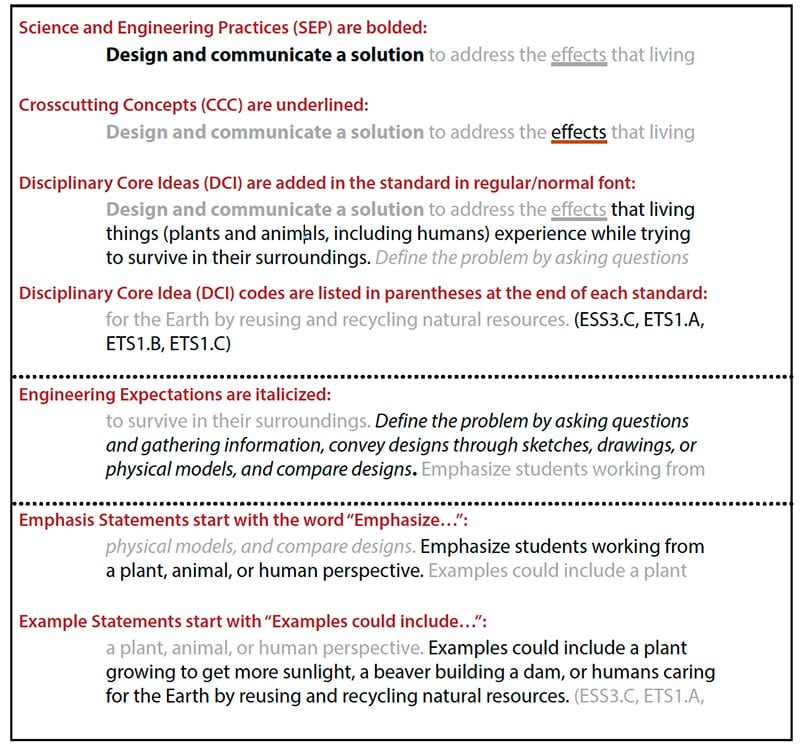

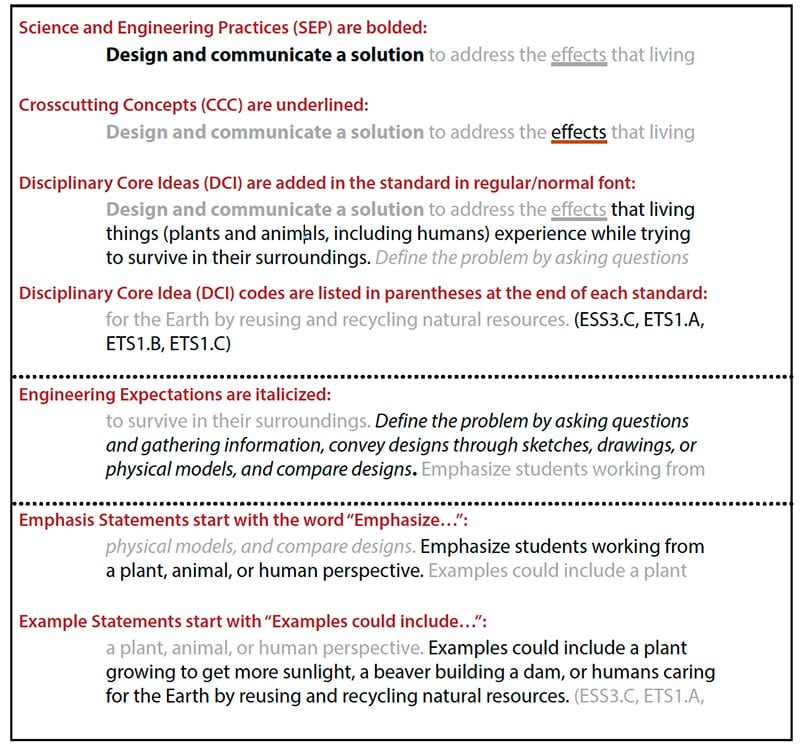

- Within each SEEd Standard Science and Engineering Practices are bolded.

- Crosscutting Concepts are underlined.

- Disciplinary Core Ideas are added to the standard in normal font with the relevant DCIs codes from the K–12 Framework (indicated in parentheses after each standard) to provide further clarity.

- Standards with specific engineering expectations are italicized.

- Many standards contain additional emphasis and example statements that clarify the learning goals for students.

- Emphasis statements highlight a required and necessary part of the student learning to satisfy that standard.

- Example statements help to clarify the meaning of the standard and are not required for instruction.

An example of a SEEd standard:

- Standard K.2.4 Design and communicate a solution to address the effects that living things (plants and animals, including humans) experience while trying to survive in their surroundings. Define the problem by asking questions and gathering information, convey designs through sketches, drawings, or physical models, and compare designs. Emphasize students working from a plant, animal, or human perspective. Examples could include a plant growing to get more sunlight, a beaver building a dam, or humans caring for the Earth by reusing and recycling natural resources. (ESS3.C, ETS1.A, ETS1.B, ETS1.C)

Each part of the above SEEd standard is identified in the following diagram:

Goal of the SEEd Standards

The Utah SEEd Standards is a research-grounded document aimed at providing accurate and appropriate guidance for educators and stakeholders. But above all else, the goal of this document is to provide students with the education they deserve, honoring their abilities, their potential, and their right to utilize scientific thought and skills for themselves and the world that they will build.

1 National Research Council. 2012. A Framework for K–12 Science Education: Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Core Ideas. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13165. This consensus research document and its chapters are referred to throughout this document as a research basis for much of Utah’s SEEd standards.

2 Most Utah SEEd Standards are based on the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS Lead States. 2013. Next Generation Science Standards: For States, By States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press) http://www. nextgenscience.org

Introduction

The third-grade SEEd standards provide a framework for students to analyze and interpret

data to reveal patterns that indicate typical weather conditions expected during a particular

season. Students develop and use models to describe changes that organisms go through

during their life cycle. Students plan and carry out investigations that provide evidence of the

effects of balanced and unbalanced forces on the motion of an object. Additionally, students

design solutions to problems that exist in these areas.

Core Standards of the Course

Strand 3.1: WEATHER AND CLIMATE PATTERNS

Weather is a minute-by-minute, day-by-day variation of the atmosphere's condition on a local scale. Scientists record patterns of weather across different times and areas so that they can make weather forecasts. Climate describes a range of an area's typical weather conditions and the extent to which those conditions vary over a long period of time. A variety of weatherrelated hazards result from natural processes. While humans cannot eliminate natural hazards, they can take steps to reduce their impact.

Standard 3.1.1

Analyze and interpret data to reveal patterns that indicate typical weather conditions expected during a particular season. Emphasize students gathering data in a variety of ways and representing data in tables and graphs. Examples of data could include temperature, precipitation, or wind speed. (ESS2.D)

Standard 3.1.2

Obtain and communicate information to describe climate patterns in different regions of the world. Emphasize how climate patterns can be used to predict typical weather conditions. Examples of climate patterns could be average seasonal temperature and average seasonal precipitation. (ESS2.D)

Standard 3.1.3

Design a solution that reduces the effects of a weather-related hazard. Define the problem, identify criteria and constraints, develop possible solutions, analyze data from testing solutions, and propose modifications for optimizing a solution. Examples could include barriers to prevent flooding or wind-resistant roofs. (ESS3.B, ETS1.A, ETS1.B, ETS1.C)

Strand 3.2: EFFECTS OF TRAITS ON SURVIVAL

Organisms (plants and animals, including humans) have unique and diverse life cycles, but they all follow a pattern of birth, growth, reproduction, and death. Different organisms vary in how they look and function because they have different inherited traits. An organism's traits are inherited from its parents and can be influenced by the environment. Variations in traits between individuals in a population may provide advantages in surviving and reproducing in particular environments. When the environment changes, some organisms have traits that allow them to survive, some move to new locations, and some do not survive. Humans can design solutions to reduce the impact of environmental changes on organisms.

Standard 3.2.1

Develop and use models to describe changes that organisms go through during their life cycles. Emphasize that organisms have unique and diverse life cycles but follow a pattern of birth, growth, reproduction, and death. Examples of changes in life cycles could include how some plants and animals look different at different stages of life or how other plants and animals only appear to change size in their life. (LS1.B)

Standard 3.2.2

Analyze and interpret data to identify patterns of traits that plants and animals have inherited from parents. Emphasize the similarities and differences in traits between parent organisms and offspring and variation of traits in groups of similar organisms. (LS3.A, LS3.B)

Standard 3.2.3

Construct an explanation that the environment can affect the traits of an organism. Examples could include that the growth of normally tall plants is stunted with insufficient water or that pets given too much food and little exercise may become overweight. (LS3.B)

Standard 3.2.4

Construct an explanation showing how variations in traits and behaviors can affect the ability of an individual to survive and reproduce. Examples of traits could include large thorns protecting a plant from being eaten or strong smelling flowers to attracting certain pollinators. Examples of behaviors could include animals living in groups for protection or migrating to find more food. (LS2.D, LS4.B)

Standard 3.2.5

Engage in argument from evidence that in a particular habitat (system) some organisms can survive well, some survive less well, and some cannot survive at all. Emphasize that organisms and habitats form systems in which the parts depend upon each other. Examples of evidence could include needs and characteristics of the organisms and habitats involved such as cacti growing in dry, sandy soil but not surviving in wet, saturated soil. (LS4.C)

Standard 3.2.6

Design a solution to a problem caused by a change in the environment that impacts the types of plants and animals living in that environment. Define the problem, identify criteria and constraints, and develop possible solutions. Examples of environmental changes could include changes in land use, water availability, temperature, food, or changes caused by other organisms. (LS2.C, LS4.D, ETS1.A, ETS1.B, ETS1.C)

Strand 3.3: FORCE AFFECTS MOTION

Forces act on objects and have both a strength and a direction. An object at rest typically has multiple forces acting on it, but they are balanced, resulting in a zero net force on the object. Forces that are unbalanced can cause changes in an object's speed or direction of motion. The patterns of an object's motion in various situations can be observed, measured, and used to predict future motion. Forces are exerted when objects come in contact with each other; however, some forces can act on objects that are not in contact. The gravitational force of Earth, acting on an object near Earth's surface, pulls that object toward the planet's center. Electric and magnetic forces between a pair of objects can act at a distance. The strength of these non-contact forces depends on the properties of the objects and the distance between the objects.

Standard 3.3.1

Plan and carry out investigations that provide evidence of the effects of balanced and unbalanced forces on the motion of an object. Emphasize investigations where only one variable is tested at a time. Examples could include an unbalanced force on one side of a ball causing it to move and balanced forces pushing on a box from both sides producing no movement. (PS2.A, PS2.B)

Standard 3.3.2

Analyze and interpret data from observations and measurements of an object's motion to identify patterns in its motion that can be used to predict future motion. Examples of motion with a predictable pattern could include a child swinging on a swing or a ball rolling down a ramp. (PS2.A, PS2.C)

Standard 3.3.3

Construct an explanation that the gravitational force exerted by Earth causes objects to be directed downward, toward the center of the spherical Earth. Emphasize that "downward" is a local description depending on one's position on Earth. (PS2.B)

Standard 3.3.4

Ask questions to plan and carry out an investigation to determine cause and effect relationships of electric or magnetic interactions between two objects not in contact with each other. Emphasize how static electricity and magnets can cause objects to move without touching. Examples could include the force an electrically charged balloon has on hair, how magnet orientation affects the direction of a force, or how distance between objects affects the strength of a force. Electrical charges and magnetic fields will be taught in Grades 6 through 8. (PS2.B)

Standard 3.3.5

Design a solution to a problem in which a device functions by using scientific ideas about magnets. Define the problem, identify criteria and constraints, develop possible solutions using models, analyze data from testing solutions, and propose modifications for optimizing a solution. Examples could include a latch or lock used to keep a door shut or a device to keep two moving objects from touching each other. (PS2.B, ETS1.A, ETS1.B, ETS1.C)

http://www.uen.org - in partnership with Utah State Board of Education

(USBE) and Utah System of Higher Education

(USHE). Send questions or comments to USBE

Specialist -

Jennifer

Throndsen

and see the Science - Elementary website. For

general questions about Utah's Core Standards contact the Director

-

Jennifer

Throndsen.

These materials have been produced by and for the teachers of the

State of Utah. Copies of these materials may be freely reproduced

for teacher and classroom use. When distributing these materials,

credit should be given to Utah State Board of Education. These

materials may not be published, in whole or part, or in any other

format, without the written permission of the Utah State Board of

Education, 250 East 500 South, PO Box 144200, Salt Lake City, Utah

84114-4200.

http://www.uen.org - in partnership with Utah State Board of Education

(USBE) and Utah System of Higher Education

(USHE). Send questions or comments to USBE

Specialist -

Jennifer

Throndsen

and see the Science - Elementary website. For

general questions about Utah's Core Standards contact the Director

-

Jennifer

Throndsen.

These materials have been produced by and for the teachers of the

State of Utah. Copies of these materials may be freely reproduced

for teacher and classroom use. When distributing these materials,

credit should be given to Utah State Board of Education. These

materials may not be published, in whole or part, or in any other

format, without the written permission of the Utah State Board of

Education, 250 East 500 South, PO Box 144200, Salt Lake City, Utah

84114-4200.

Course Introduction

Course Introduction

UTAH EDUCATION NETWORK

UTAH EDUCATION NETWORK

Justin

Justin Braxton

Braxton Dani

Dani Kayla

Kayla Katie

Katie Lora

Lora Rob

Rob Val

Val